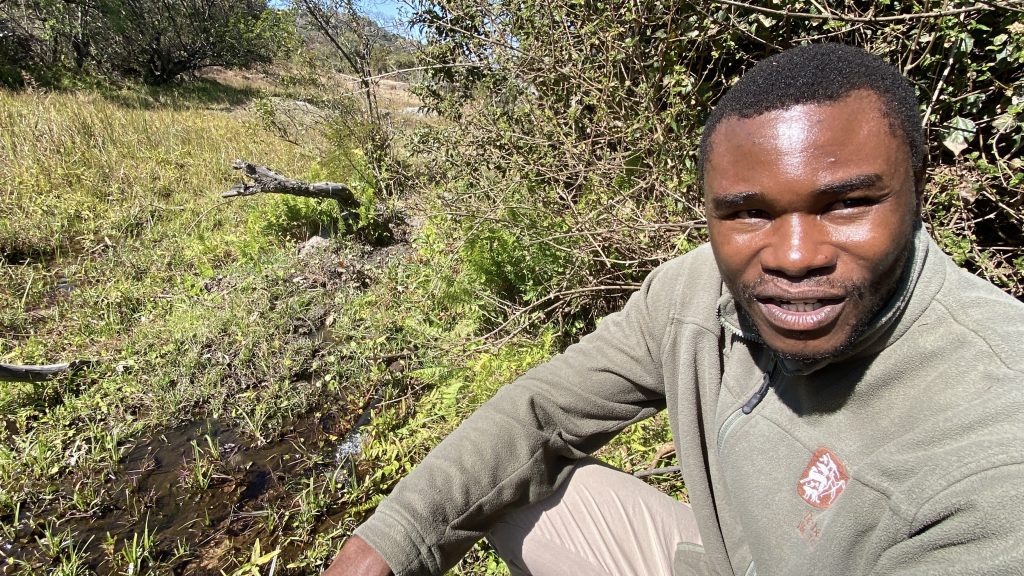

Legislator Sam Matema washing his hands demonstrating how clean the water at Morning Glory wetland in Matabeleland south was, during a tour recently

By John Cassim

Zimbabwean legislators are pushing for a significant change at the upcoming 15th Conference of Parties (COP15) to the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, to be hosted in Victoria Falls in July. They’re demanding that authorities must ensure ordinary villagers are included, allowing them to share their first-hand experiences with wetlands.

This call emerged during a feedback meeting organized by BirdLife Zimbabwe. Senator Jerry Gotora, a former Chairman and Founder of Painted Dog Conservation in Hwange, emphasized the impact of local voices.

“If we bring people from Makoni District, for example, to the Ramsar Convention to speak about the effects of wetland degradation, they’ll be heard more effectively than those from cities like Bulawayo and Harare,” Senator Gotora explained, drawing on his background. “I can assure you they will be listened to.”

He drew a parallel to the CITES Convention: “If all of us the academics and converted attend a CITES meeting and just talk and shout, no one listens. But if you take villagers from the ground to CITES, I can tell you we’ll be listened to, and the Convention will fund us. That’s how we won the down listing of elephants—we brought villagers from Kenya to South Africa, and their voices led to the down listing.” Senator Gotora spoke passionately, detailing how a lack of oversight by local councils has led to the deterioration of some Zimbabwean wetlands.

He challenged his fellow legislators with critical questions: “What does it mean to host such an important COP, perhaps once in a hundred years? I was privileged to attend two COPs, Kyoto and Paris. What should we, as the senate, be doing?”

A magnificent view of water flowing on top of granite rocks at Diana’s Pool one of the tourism attraction in Matabeleland South.

Senator Gotora reminisced about the Driefontein wetlands in Manicaland, once home to unique bird species found only there and in Eswatini. He lamented that farmers in Makoni can no longer cultivate crops like yams, sugarcane, and bananas, which historically relied on wetland water. He attributed this decline to the abolishment of intensive conservation areas (ICAs) when the Environmental Management Agency (EMA) was created.

Calls for Legal Reform and Transparency

Other legislators urged the government to amend existing laws, emphasizing the need for legislation that effectively protects wetlands, which they called “the lungs of our water reservoirs.”

“Wetlands are our silent defenders against droughts and our frontline buffers against climate change,” stated legislator Mutsa Murombedzi from the Tourism portfolio committee. “In tourism, we say wetlands are not wastelands; they are wonderlands.”

The meeting saw representation from the Portfolio Committees of Environment, Climate and Wildlife, Tourism, Justice Legal and Parliamentary Affairs, Local Government and Public Works, as well as the Senate Thematic Committee on Climate. It followed wetland tours in Harare, Chinhoyi, and Matabeleland South recently.

Tafadzwa Ticharwa from Dambari Wildlife Trust explaining how the community in Matobos area are involved in the preservation of their wetlands.

Meanwhile, Fiona Illif, an Environmental and Human Rights Lawyer, highlighted the necessity of amending the existing EMA Act.

“There’s no independent body reviewing applications to construct in wetlands and genuinely considering the environmental impact of proposed projects,” she explained. “The public consultation process is often a mere rubber-stamping exercise. Often, Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) submit extensive reports detailing why developments shouldn’t proceed, but these aren’t considered, and Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) are simply approved, even on Ramsar sites.”

She further explained that while the EIA process technically allows for public participation, it lacks transparency. “It’s very difficult to know if an appeal has been lodged or how it’s being processed. You simply send a letter to the minister and await a decision. In the meantime, development continues; it doesn’t stop the project.”

Illif also pointed out the significant financial burden involved: “You need substantial funds. First, you appeal to the minister, then file a separate application to suspend the development. You also need to appeal any other permits, like mining claims or development permits. And then you need to see the entire process through.””If the minister dismisses your appeal, you then have to go to the Administrative Court, the Supreme Court, in addition to the High Court application to suspend development. So, it’s very expensive and not truly accessible to the public,” Fiona concluded.